Color Her Celebrated: A Conversation with Our 2025 ASCAP-Bob Harrington Lifetime Achievement Recipient, Sandy Stewart

Hesitation was never something that could hold singer Sandy Stewart back—not when it came to her career. The 2025 recipient of the ASCAP-Bob Harrington Lifetime Achievement Bistro Award knew, even as a kid growing up in Philadelphia, just what her life’s vocation should be.

I recently had the honor of meeting with Stewart at her Upper East Side apartment, where she shared some of her musical memories, including very early ones:

From the time I was, oh, gosh, four or five years old, I remember, vividly, sitting next to the radio—of course, there was no TV as yet—listening to all the singers of the day and memorizing all the songs. … By the time I was 12, I was working with local bands as the singer. They didn’t know I was 12, but my mother would make me up. And they’d pay me five dollars for the night. And five dollars, in those days, was a lot of money.

It may sound like a Madame Rose and Dainty June scenario, but Stewart insists that while her mother was supportive, she wasn’t a pushy stage mom. It was young Sandy herself who pressed to get the work. Nobody else in the family had shown serious musical inclinations or harbored visions of show-biz glory.

True, her father had fantasized about being a drummer for a big band—specifically, Benny Goodman’s big band— but that was just a fleeting dream. When Stewart booked a tour as a singer with the Goodman band, her father was proud, impressed, and maybe a little envious. But when she returned home from the gig, she told him, “You wouldn’t have enjoyed it so much.”

She explained to him how Goodman had publicly humiliated jazz pianist Teddy Wilson during a show in Colorado Springs. Wilson had been someone Stewart relied on during the rather tumultuous tour.

Benny turned around to Teddy, and in a stage whisper, said, “You stink.” Teddy… apparently wasn’t too shocked about Benny’s rhetoric. Gentleman that he was, he just looked at the audience, bowed his head, took the top that goes over the keys, put it down gently, nodded to me, nodded to the audience, got in his Rolls-Royce, and drove back to New York. And I ran backstage and said, “Please don’t leave me. Please.” I needed him.

I forgot who Benny hired to replace Teddy, but that’s typical of what used to go on. Kind of like what’s going on in the Capitol these days. People are just getting fired for no reason, and they’re leaving with no explanation….

Before this incident, Stewart had already launched her recording career. Her first single was made in New York City before she moved there from Philadelphia. She was then age 15.

Dick Clark was a Philadelphia boy, so he promoted it. He had a studio as big as this table, with just a turntable and a microphone, and he would interview different people that came in, to program their records and promote them. … The name of the song—it was a terrible song—was “Do Ya! Do Ya!”

She sings a few bars for me:

“Do ya, do ya, do ya, do ya, wanna, wanna wanna, wanna…”

It was awful. The Philadelphia disc jockeys played it day and night. They pushed that record. It was embarrassing. It was a terrible, terrible song. But I got into the recording business, so that was important.

Stewart recorded for the Atlantic label, as well as for Epic Records (a subsidiary of Columbia Records). In those days, she says, kids new to the business customarily recorded only singles if they hadn’t yet scored on the charts. Only then would they be given a chance with an album. “Nowadays, gals do their own thing,” she notes. “They spend money on doing a CD, which I think is wonderful. But it’s expensive to do something like that.”

It was only after she introduced what would become John Kander and Fred Ebb’s first-ever hit song, “My Coloring Book,” in 1962—earning a Grammy nomination—that a studio would release a whole album of Sandy Stewart music.

Learning to Play Straight, and Other Big Breaks

Before the “Coloring Book” breakthrough, however, she appeared in early TV shows and in the movies. Well, in a movie.

While still a highschooler, she moved to New York. She booked a job on Ernie Kovacs’ morning television show. She would take over for Kovacs’ wife, Edie Adams, who was signed for Broadway’s Wonderful Town. Stewart moved into the Barbizon Hotel for Women, a “safe haven” for young, single women in arts and entertainment careers. She continued her academic studies at the Rhodes Preparatory school on East 54th Street.

Kovacs’ show ran on a low budget. Stewart sang with piano only, not with a band, However, the pianists she worked with were major talents: Bernie Layton, Norman Paris, and Dick Hyman (who, incidentally, was a distant cousin of Stewart’s future husband, composer Morris “Moose” Charlap of Peter Pan fame). Kovacs had no funds to build sets for his comedy sketches. Instead, he would recycle discarded ones from other CBS programs, devising scenarios that would work with the leftover scenery.

With Kovacs, Stewart says, everything was “off the cuff.”

He would put costumes in our dressing rooms. He would say, “Just come out when we go on the air. Put the costume on, come out, and we’re gonna do a comedy act—and don’t you dare laugh.” He taught me how to be a straight man at the age of 16, 17.

On occasion, she would break up.

Sometimes it was impossible. All the cameramen were bent over laughing. I mean, all of us. And he knew he could [cause] that. But for the most part…I tried to bite my tongue and purse my lips and just not laugh out loud.

Another TV offering that featured Stewart in those early days was CBS’s The Morning Show, which ran opposite NBC’s The Today Show in the early 1950s and was led by Walter Cronkite. Merv Griffin was the “boy singer” and Stewart the “girl singer.” She recollects that a young Dick Van Dyke was the show’s weatherman. The IMDb website notes, however, that Van Dyke remembered himself as “host” of this program, with Cronkite serving as “anchorman.”

If memories of the show are fuzzy it may be because those long-ago mornings were themselves a blur:

Every morning at 6, we were all lined up in the makeup room: Walter Cronkite, Dick Van Dyke, Merv, little Sandy. We were all half asleep. We could have walked out there looking like Halloween revisited, because nobody ever looked in the [makeup] mirror. It gave us a chance to close our eyes.

with Chuck Berry and Alan Freed.

In 1959, Stewart made that one-and-only motion picture, taking the female lead in a rock-and-roll feature called Go, Johnny Go! She starred opposite Jimmy Clanton, with Chuck Berry in a key role. Filmed in five days at Hal Roach’s studio in California, the film was, much like the Kovacs show, produced on a shoestring budget. Stewart, who soloed on the sassy song “Playmates” and one other number in the picture, supplied her own costumes, with some help from an expert.

I had a gal that was living at the Barbizon who was my friend…a top model at Vogue at the time, and she went shopping with me. She said, “These are the clothes that you have to wear for that.” And she was right, because they were very simple, ageless in style. She said, “That’s what you want. … You don’t want to look like a rock-and-roller.” That wasn’t the part, anyway. [My character] was an ingenue-wannabe actor-singer.

Go, Johnny Go! was a popular film with young audiences (and it would become a cult film of sorts with later generations). At one point Stewart was offered a five-picture film deal. She would turn it down, in part because, as a self-described “ham,” she preferred live performance to film work. She liked the immediate feedback. But also, by 1962, she would be married to Moose Charlap and would become focused on raising a family with him rather than on show business.

Between 1959 and 1962, however, there were other heights yet to hit.

From Big Name Comics’ Opening Act to Ed Sullivan and Perry Como

Once her high-school diploma was duly earned, Stewart was able to accept engagements outside of New York and Philadelphia. Often, she was an opening act for comics—something she loved. She shared the bill with the likes of Alan King, George Burns, Henny Youngman, Joey Bishop, the Ritz Brothers, and a young Bob Newhart.

It was at a Ritz Brothers show in New York that she received a note backstage from television showman Ed Sullivan, asking her to meet him and his wife, Sylvia, at their table after the show, to help them resolve a “bet.”

I sat down with them at their table. He said, “Sylvia and I have a bet on whether you come from a long-time show business family. Vaudeville. The whole thing.”

And I said, “Who’s betting what?”

He said, “Sylvia said ‘no’—you’re just you. This is you. This is not anyone else.”

And I said, “Sylvia won the bet, Mr. Sullivan. I’m sorry.”

“Well, that’s all right, dear,” he said. “I want to sign you for six shows.”

The surprise offer was not only lucrative, but it also helped her get other bookings.

Her first time working with singer Perry Como was on a 1960 Bing Crosby television program on which she and dancer Elaine Dunn performed with Perry and Bing. She remembers both Como and Crosby as being very kind to her. This appearance eventually led to her being hired at NBC as one of five Kraft Music Hall Players—regulars on the popular Como-hosted series. The other four? Kaye Ballard (who became a dear friend), Don Adams, Canadian comic Jack Duffy, and Paul Lynde.

Perry was very generous with us. Not only did we do comedy sketches together, but we were also featured as a separate entity during the show on occasion. He would have Paul do a routine; he would have Kaye do a song from a Broadway show that she may have been in at the time.

Which is how “Coloring Book” came to be. We were in rehearsal one day, and Fred Ebb and John Kander at that time were writing special material for Kaye. They walked into rehearsal, and they were all excited. They said, “Kaye, we have a great song for you to do, the next time Perry lets you do a single performance.” And she said, “Let me see the song.” Kaye could…play the flute, and she could read [music] very well. She said, “You know what? They’re not gonna believe me doin’ this song. Give it to Sandy.”

It became a big hit. Streisand covered it. Kitty Kallen covered it. But I was the one that got nominated for the Grammy.

Moose Charlap had helped ensure that Stewart got to the recording booth first with “My Coloring Book.” He called his former roommate, top-drawer musical arranger Don Costa, immediately after the song’s debut on the Como show. “Don wrote the chart on it, and we recorded it the following week,” Stewart recalls.

The song turned out to be her only big success on the Billboard charts. “When I do a cabaret act,” she says, “I always say, ‘This song was Kander and Ebb’s very first hit. And my last.’”

Losing the Love of Her Life…But, After a While, a New Start

After the marriage to Charlap, Stewart’s family grew. In the mid-1960s daughter Katherine and son Bill joined two children of Moose’s from a previous marriage. By about 1970, Stewart had phased out her club-singing career, dropping her affiliation with William Morris and letting her manager go. (She continued doing voiceover work.) She took “a lot of flak” for her decision, as she had continued to be in demand as an entertainer. “They said, ‘You’re crazy. This is like a once-in-a-lifetime thing. And, you know, you’re not getting any younger’ And I said, ‘No. My children are more important.’”

demo composition written by Charlap.

It was a happy time. At one point, the family moved to California, where Charlap supplied music for ClownAround, a musical that was slated to star Gene Kelly. The Charlaps rented a house near Beverly Hills. The home was, says Stewart, like a stage set depicting an old castle.

It had these pillars and a sunken living room. And every time I walked in, I said, “This is ridiculous!” Gene came over one day to have a meeting with Moose, and I saw the pillar. I saw Gene. I said, “Do it for me. Please do it for me.” And he said, “OK.” And he did it. He put his arm around the pillar, and he did “Singin’ in the Rain.” Oh God, it was wonderful.

Unfortunately, the good times stopped abruptly when Moose Charlap passed away from complications from type 1 diabetes (also known as “juvenile diabetes”) in 1974. Stewart was shattered, and she knew that with four children depending on her for support, she would need to go back to work. “I just did it,” she says. “You do what you have to do in life. And it was fine.”

(The phrase “it was fine” seems to be a kind of mantra for Stewart, suggesting the peace that can come with accepting the good and not fretting too much about the not-so-good. She will say these words repeatedly during the course of our chat.)

She began to sing in public again, but the music scene she’d known was undergoing some changes. While there was still room for her kind of music in a sphere dominated by rock-and-roll and its outgrowths, the gigs that had been known simply as “club singing” were beginning to give way to this thing called cabaret.

She found singing work on her own, without an agent. She eventually called Donald Smith, who helped her explore the evolving music scene. Pianist Mike Renzi became a valued accompanist.

After a time, she began booking once more for out-of-town engagements as well as local ones. On the side, she sang a lot of jingles for TV commercials. Her voice was heard in a notable Enjoli perfume ad, in which she channeled Peggy Lee. And she sang, “Looks like a pump, feels like a sneaker” in a spot for Easy Spirit footwear.

You saw these young basketball players—females—in these high-heeled shoes. … It was their first shot at promoting these Easy Spirit shoes. Now they’re a huge company. And I wear all their flats. No heels anymore!

Fast Forward: An Album and “The Umbilical Connection”

In more recent years, Stewart recorded some solo albums: her first since the My Coloring Book disc back in the 1960s.

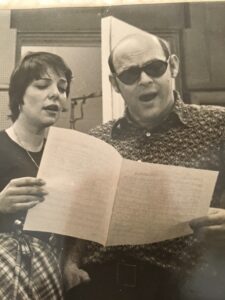

A career highlight was a vinyl album called Sandy Stewart Sings Jerome Kern with Dick Hyman at the Piano, marking the Kern centenary in 1985. She was accompanied on piano—exquisitely—by her distant cousin-in-law. Several years later, he contacted her about reissuing the album as a CD. However, a few more songs would have to be recorded for the new format.

I remember going into the studio and saying, “Gee, I hope I sound the same.” Because my voice [had] dropped—as you get older, your voice drops. But [Dick] said, “I can’t believe it. You sound exactly the same on the extensions.”

As Bill Charlap and his half-brother, bassist Tom Charlap, grew older, they began performing with Stewart in clubs, and in 1994 their talents were displayed on a CD called Sandy Stewart & Family. It included several Cole Porter cuts. (Stewart remains a devoted Porter fan: “He was the sexiest lyricist ever. Nobody wrote a lyric sexier than Cole Porter. Ever. Ever.”)

Later came two more albums with son Bill, by then known as a world-class jazz pianist. Love Is Here to Stay was released in 2005 and Something to Remember in 2013.

The umbilical connection between the two performers has made for a peculiarly effective collaboration. Bill knows just when Sandy will take a breath, when and how she’ll execute a crescendo or decrescendo. Sandy senses what Bill will do at the keys. After all, she’s seen him learn about and master them since he could barely reach them.

She attributes the longevity of her career to singing lessons she took in New York early in her career:

I studied opera for a number of years, for technique purposes. To learn proper breathing, creating a vibrato, taking it away, doing a crescendo—all those technical things that a horn player would learn how to do. And it has helped me continue to sing in my eighties. Because I know technically what to do. And I also know what I can’t do anymore.

Stephen Holden described the artistry of Sandy Stewart whimsically in a 2007 New York Times review of a show she and son Bill performed in the Oak Room of the Algonquin Hotel:

“With her aura of solidity and calm, she suggests a tree that has buried its roots into the stage. As the rain and wind blow through the branches, the heavy weather registers. At the same time, you sense that its roots are so deeply embedded that there is no danger of its toppling.“

She had clearly come a long way from “Do Ya, Do Ya.”

Stewart is looking forward to being at Gotham Comedy Club to pick up her Bistro award on April 14 and to take the stage once more. Bill Charlap will be there to introduce and accompany her, along with daughter Katherine (who has a birthday that day) and beloved daughter-in-law, pianist-composer Renee Rosnes.

She has not performed in public since a show at Birdland two summers ago. The recipient of a Mabel Mercer Award at the 2017 Cabaret Convention, she notes that she’s lately taken a page from the revered Mercer.

“Unfortunately, I’ve had a couple of spinal surgeries over the years, so I have to sit—like Mabel,” she notes. “I became a ‘Mabel person’— sitting and singing.”

“But it was fine,” she adds.

###

About the Author

Mark Dundas Wood is an arts/entertainment journalist and dramaturg. He began writing reviews for BistroAwards.com in 2011. More recently he has contributed "Cabaret Setlist" articles about cabaret repertoire. Other reviews and articles have appeared in theaterscene.net and clydefitchreport.com, as well as in American Theatre and Back Stage. As a dramaturg, he has worked with New Professional Theatre and the New York Musical Theatre Festival. He is currently literary manager for Broad Horizons Theatre Company.